Scaling laws explain how the performance of large language models (LLMs) improves as model size, dataset size, and compute power increase. These predictable patterns, based on power-law relationships, allow researchers to optimize resources and forecast outcomes without trial and error. Key takeaways include:

- Model size matters most: Larger models trained on moderate data often outperform smaller, fully trained ones.

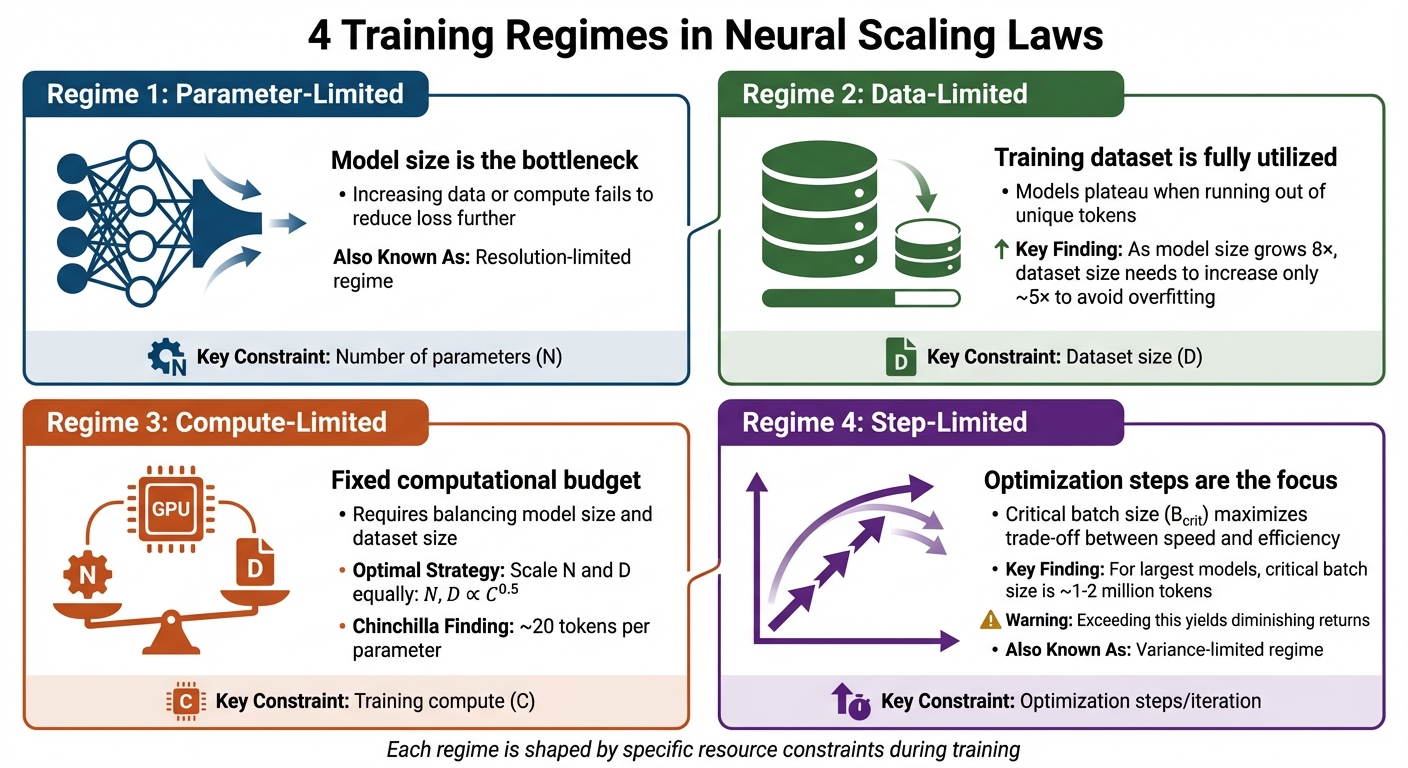

- Four training regimes: Performance is limited by parameters, data, compute, or training steps depending on constraints.

- Chinchilla scaling insights: Doubling model size requires doubling training tokens for optimal efficiency.

- Emergent abilities: Some capabilities appear suddenly at certain scales, challenging linear predictions.

Scaling laws serve as a roadmap for designing LLMs, emphasizing resource allocation over architecture tweaks. Researchers now focus on balancing model size, data, and compute for efficient training and improved downstream performance.

Understanding LLM Chinchilla Scaling Laws – Why Bigger Isn’t Always Better!

sbb-itb-f73ecc6

Core Principles of Neural Scaling Laws

Four Training Regimes in Neural Scaling Laws for LLMs

The Power-Law Relationship

At the core of neural scaling laws lies a straightforward yet powerful mathematical relationship: as model parameters (N), dataset size (D), and training compute (C) increase, test loss decreases in a predictable power-law fashion. This pattern holds steady across an impressive range – spanning over seven orders of magnitude.

The general formula for this relationship is:

L(X) ≈ (X₍c₎ / X)^(α₍X₎),

where X represents N, D, or C. For Transformer models, doubling the number of parameters typically reduces the loss by about 5%, with scaling exponents of approximately 0.076 for parameters and 0.095 for dataset size.

DeepMind’s Chinchilla research refined this understanding further with the equation:

L(N, D) = E + A/N^(α) + B/D^(β),

where E represents irreducible loss, essentially the entropy of the data. In March 2022, this framework was validated by training 400 models, ranging from 70 million to 16 billion parameters, on datasets containing up to 500 billion tokens.

"Performance depends most strongly on scale, which consists of three factors: the number of model parameters N, the size of the dataset D, and the amount of compute C used for training."

4 Scaling Regimes

Training scenarios can be categorized into four distinct regimes, each shaped by specific constraints:

- Parameter-Limited Regime: Also known as the resolution-limited regime, this occurs when increasing data or compute fails to reduce the loss further because the model size itself is the bottleneck.

- Data-Limited Regime: This regime emerges when the training dataset is fully utilized. Even the largest models hit a plateau if they run out of unique tokens to learn from. Kaplan’s research suggests that as model size grows 8×, the dataset size only needs to increase roughly 5× to avoid overfitting.

- Compute-Limited Regime: Here, a fixed computational budget requires careful balancing between model size and dataset size. According to Chinchilla research, the best results come from scaling N and D equally, following the relationship N, D ∝ C^(0.5) – roughly 20 tokens per parameter.

- Step-Limited Regime: Also referred to as the variance-limited regime, this focuses on optimization steps. A critical batch size (B₍crit₎) exists that maximizes the trade-off between training speed and compute efficiency. For the largest models, this critical batch size is around 1–2 million tokens. Exceeding this size yields diminishing returns.

While these regimes provide a clear framework, they also highlight the complexities and challenges that remain.

Current Limitations and Open Questions

Despite their reliability, scaling laws have limitations. Most empirical validations so far have been conducted on models with up to 33 billion parameters. In March 2024, researchers at Meituan Inc. confirmed that OpenAI’s original formulations hold at this scale, though they observed that constant coefficients can vary depending on tokenization methods and data distribution.

Whether these laws will apply to models far beyond the GPT-4 scale remains uncertain. Random parameter initializations can lead to loss fluctuations of up to 4%, while improvements in pretraining procedures often result in loss changes between 4% and 50%. Additionally, researchers have identified broken neural scaling laws (BNSL), where certain metrics follow piecewise linear patterns in log–log space, exhibiting S-shaped behavior. This suggests that some capabilities might emerge in sudden leaps rather than through gradual progress. Current studies are exploring how factors like data composition and mixture ratios influence the constants in scaling equations.

A meta-analysis conducted by MIT and IBM researchers in October 2024, covering 485 pretrained models, revealed that final loss can often be accurately predicted after just one-third of the training process.

How Scaling Laws Are Used in AI Research

Pretraining Loss and Downstream Task Performance

In AI research, pretraining cross-entropy loss has often been used to predict downstream task performance, with the assumption that lower loss translates to better results. However, this method can lead to compounding errors when forecasting benchmark outcomes.

In December 2025, Apple researchers conducted a study involving 130 models, scaling up to 17 billion parameters trained on 350 billion tokens. They demonstrated that log accuracy on benchmarks scales predictably with training FLOPs, achieving a Mean Absolute Error of 0.0203. Highlighting the importance of their findings, they noted:

"The direct approach extrapolates better than the previously proposed two-stage procedure, which is prone to compounding errors." – Jakub Krajewski et al., Apple

By predicting task performance directly – without relying on pretraining loss – researchers improved the accuracy of their forecasts. For multiple-choice benchmarks, normalizing accuracy to account for random guessing ensured the power law held across the entire training range.

These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing training strategies, especially when working within fixed computational limits.

Compute-Optimal Training Strategies

Scaling laws also help researchers determine the best way to balance model size and dataset size when computational resources are limited. In March 2022, DeepMind trained 400 models across a wide range of scales and found that many large language models (LLMs) are undertrained.

A standout example is Chinchilla, a 70-billion-parameter model trained on 1.4 trillion tokens – four times more data than the 280-billion-parameter Gopher model. Despite using the same compute budget, Chinchilla achieved an average MMLU accuracy of 67.5%, outperforming Gopher by 7%. The study revealed a key principle: for every doubling of model size, the number of training tokens should also double.

This approach provides a clear strategy for resource allocation. Larger models can reach target performance with fewer training steps. When compute resources are tight but data is plentiful, the focus should shift to increasing model size rather than extending training duration.

How Scaling Laws Shape LLM Development

Scaling Laws as a Development Roadmap

Scaling laws have become more than just tools for predicting performance – they now serve as a blueprint for designing and deploying large language models (LLMs). These laws provide AI researchers with a clear understanding of how performance scales with increases in compute power, data, and model size. Instead of relying on trial-and-error experiments with different architectures, researchers can use scaling laws to predict performance trends, which follow a power-law relationship spanning over seven orders of magnitude. This clarity allows labs to plan precisely how much investment is needed to reach specific performance goals.

The implications for model design are profound. The focus has shifted toward increasing the number of parameters, growing datasets, and securing more compute resources. Interestingly, architectural hyperparameters – like the specific details of a model’s structure – are far less important than its overall scale. As Jared Kaplan from OpenAI explains:

"Larger models are significantly more sample-efficient, such that optimally compute-efficient training involves training very large models on a relatively modest amount of data and stopping significantly before convergence."

This insight has transformed industry-wide training strategies. Instead of fully training medium-sized models, labs now prioritize training much larger models on smaller datasets, optimizing compute efficiency. The approach also justifies the enormous investments required for scaling. For example, a 10x increase in compute demands roughly a 3.1x increase in both model size and training data to maintain efficiency. This predictable relationship not only informs architectural decisions but also sets the stage for uncovering new, unforeseen capabilities.

Emergence of New Capabilities

Scaling laws don’t just guide performance predictions – they also reveal how entirely new abilities emerge when models reach a certain size. While metrics like cross-entropy loss improve predictably, some capabilities appear suddenly, rather than gradually, as models hit critical thresholds. These shifts resemble sigmoid-like jumps rather than smooth progressions.

Jason Wei and his team at Google captured this phenomenon across various benchmarks:

"We consider an ability to be emergent if it is not present in smaller models but is present in larger models. Thus, emergent abilities cannot be predicted simply by extrapolating the performance of smaller models."

This discovery has changed how AI labs approach development. Beyond traditional pretraining, there’s now significant investment in post-training scaling – such as fine-tuning, distillation, and reinforcement learning – and test-time scaling, which involves allocating additional compute during inference for tasks requiring complex reasoning. For instance, post-training derivative models may demand up to 30x more compute, while test-time scaling for challenging queries can require over 100x the compute of a single inference pass. Models like OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek‘s R1 are prime examples, employing extended reasoning during inference to tackle multi-step problems that pretraining alone cannot solve.

Key Takeaways for Researchers

Practical Lessons from Scaling Laws

When it comes to improving model performance, scaling often outweighs architecture. The key factors are the number of non-embedding parameters, the size of the dataset, and the compute budget – not specific design choices like depth-to-width ratios. This means researchers might benefit more from prioritizing resources over endless hyperparameter tuning.

For those working with limited compute resources, an interesting tactic is to train a much larger model and intentionally stop training well before it fully converges. Jared Kaplan from OpenAI highlights this approach:

"Optimally compute-efficient training involves training very large models on a relatively modest amount of data and stopping significantly before convergence".

Another important takeaway is the shift toward directly predicting downstream performance instead of relying on proxy loss metrics. This direct method avoids errors that can stack up when using indirect measures, offering more accurate and practical forecasts.

Scaling now operates across three distinct stages: pretraining, where foundational intelligence is built; post-training, which focuses on fine-tuning and domain-specific adjustments; and test-time scaling, where additional compute is used during inference to handle more complex reasoning tasks. These stages are becoming the core of evolving model development strategies.

Future Directions in Scaling Research

Looking ahead, scaling research is moving into new territory, addressing challenges that go beyond just reducing loss. The focus is shifting toward accuracy-centric models, where researchers develop direct power laws to predict downstream performance. This method has already been validated on models with up to 17 billion parameters and datasets containing 350 billion tokens. It marks a significant shift in how future model capabilities are anticipated.

Another exciting area is test-time scaling, also referred to as "long thinking." This involves allocating extra compute during inference to improve multi-step reasoning. Models like OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek’s R1 show that this strategy can significantly enhance performance on complex tasks. It suggests that the next big advancements might come as much from smarter inference techniques as from scaling up pretraining.

However, researchers must also grapple with the theoretical limits of scaling. Some challenges, like hallucination, may be inherent to the probabilistic nature of language models. As Muhammad Ahmed Mohsin explains:

"Hallucination is not a transient engineering problem but an intrinsic property of probabilistic language models".

Understanding these limitations – whether in areas like context compression, reasoning accuracy, or retrieval reliability – is crucial for setting realistic expectations about what scaling can achieve. Recognizing these boundaries will shape the future direction of research and innovation in this space.

FAQs

How do scaling laws affect the training efficiency of large language models (LLMs)?

As large language models (LLMs) increase in size, they become noticeably better at handling data more efficiently. In fact, bigger models need less computation per token to reach the same level of performance as their smaller counterparts. This insight suggests that the best way to train these models is by focusing on very large models paired with moderate-sized datasets, stopping the training process before reaching full convergence.

This approach allows researchers to make the most of their resources by carefully balancing model size, dataset volume, and computational power – achieving strong performance without wasting time or energy on overtraining.

What are the key challenges with scaling laws in large language models?

Scaling laws offer valuable insights, but they come with their own set of challenges that can limit their broader application. For starters, model architectures and training methods often vary so much that a single formula can’t account for all the differences. Adjustments usually need to be made to fit specific scenarios. On top of that, predictions can be thrown off by factors like random seed variability or the range of model sizes being analyzed. In some cases, training several smaller models can actually provide more consistent insights than focusing on just one large model.

Another hurdle is the variation in compute efficiency across different types of models. This makes it tricky to establish a unified scaling framework, especially when trying to predict behavior beyond the data you already have. Even when scaling laws seem to align well with observed trends, they don’t address some of the core limitations of large language models (LLMs). Problems like hallucinations, compressed context windows, or a decline in reasoning performance remain unresolved. These challenges underscore the importance of fine-tuning scaling approaches and recognizing the built-in constraints of these models.

Why do large language models suddenly develop new abilities as they scale?

Large language models (LLMs) can exhibit sudden leaps in their abilities instead of gradual improvements, a phenomenon comparable to a phase transition. When factors like model size, the amount of data, or computational power reach a critical point, the model undergoes a dramatic internal shift. This change enables it to perform tasks that smaller models cannot, and these advancements are often hard to predict based on earlier performance trends.

This phenomenon underscores the role of scaling laws in understanding LLM development. By studying these laws, researchers aim to predict when such breakthroughs might occur, helping to train models more efficiently and responsibly.